AUTHORS:

Karen Foster and

Louise Birdsell Bauer

EXECUTIVE

SUMMARY

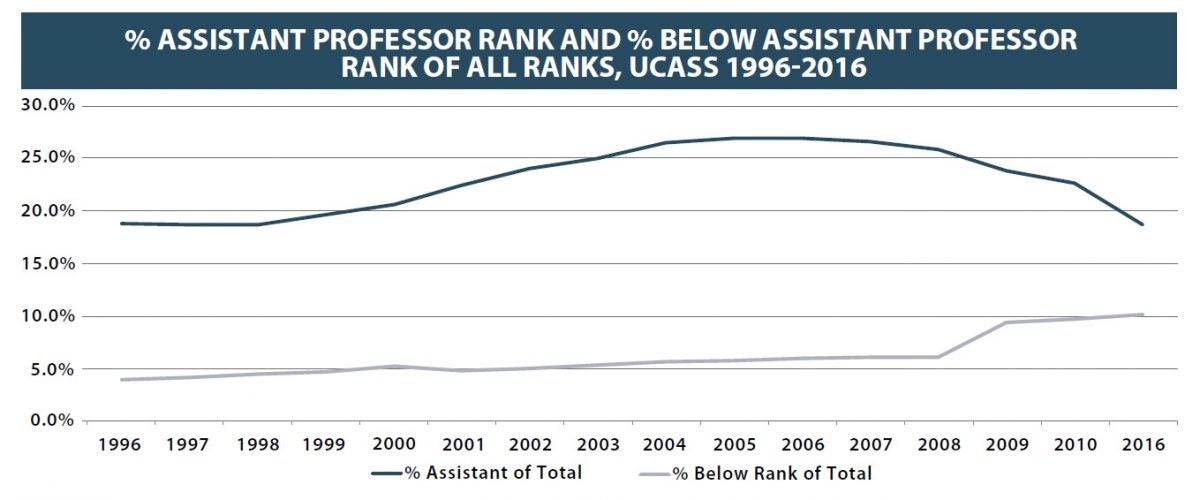

An increasing number of academic staff at universities and colleges in Canada are working in non-standard employment – working part-time, or on temporary and short-term contracts. The narrative around these gig or short-term contracts in post-secondary education (PSE) is that they serve both the institutions and the workers well. Like assumptions about Uber drivers, the story goes that contract academic staff (CAS) are just picking up extra income on the side while studying or working elsewhere. Indeed, the rise of these casual positions is often described as a benefit to workers attracted to the flexibility.

But there is another story of CAS who are seeking permanent work, shouldering immense workloads for paltry paycheques, and doing their jobs without the resources afforded to full-time and tenure-track faculty. Instead of attractive flexibility, this story is about discouraging, demoralizing precarity.

Though CAS experiences have been investigated in several provinces in recent years (Birdsell Bauer 2011; Birdsell Bauer 2018; Foster, 2016; Field and Jones, 2016), confirming the story of precarity to a large degree, we sought to assess these stories nationally by exploring the motivations, expectations, interests and working conditions of post-secondary education teachers working on contract. We also sought to go beyond this research by including demographic variables of race and sexual orientation, as well as included a number of questions to gauge the impacts of this type of academic employment on respondents’ work-life balance and their mental health. We also asked whether these academics felt that their PSE institutions were model employers and supported good jobs.

The overall findings, from 2606 respondents, paint a negative picture of highly qualified and committed academics who are underpaid, overworked, and under-resourced, and who feel excluded in the Canadian post-secondary institutions where they try to provide an excellent education to students under dismal working conditions. Specifically, we learned that:

• More than half (53%) want a tenure-track university or full-time, permanent college job, and this desire holds even for people who have been teaching for 16-20 years. Only 25% said, unequivocally, that they do not want a tenure-track or permanent, full-time academic appointment. The remainder are unsure whether or not they want a tenure-track appointment.

• Job security ranks as the top priority concern. Only 21% of respondents had non-academic full-time, permanent work. If there is a ‘majority’ group among our respondents, it is people who are trying to make a full-time career out of working at a post-secondary institution.

• The dominant CAS experience is that of people who rely on such employment to make ends meet. However, it is also clear that most cannot rely on their CAS employment alone. Most have some other form of income or feel that their current situation is unsustainable.

• Women and racialized CAS work more hours per course per week than their white male CAS colleagues and are overrepresented in lower income categories.

• 42% of CAS believe their mental health was impacted by their PSE employment. 87% of those respondents believe their mental health was been negatively impacted by their CAS employment.

• Just 19% of those surveyed think the post-secondary institutions where they work are model employers and supporters of good jobs.

These survey results challenge the stereotype of CAS as happy moonlighters. There certainly is a minority of part-time educators who feel supported and valued, who deliberately seek and appreciate the flexibility and dynamism of contract work, or who have found some stability in ongoing, renewable contracts. There are some CAS who are supplementing income from full-time non-academic jobs or easing into retirement. There are professionals who teach to share the knowledge and experience they have gained in their fields.

Yet, for a substantial number of survey respondents, part-time teaching is precarious work, characterized by income insecurity, exclusion from career development, and unrecognized and unremunerated contributions. These respondents tell us the non-permanent terms of their contracts make it difficult for them to make long-term plans or investments. They relay how the non-permanence of their contracts makes it difficult to supervise students and contribute new knowledge as trained researchers and scientists.

To read on, go to CAUT CAS Report